Hoarding, collection, memory

Romy Day Winkel

When I was a kid I wished for a companion. This wish was projected upon many dolls and stuffed animals in passing. I had fantasies in which I would travel with one of them by my side. At the end of our journey its hair would be messy, its face covered in dust. I would need to scratch out the sand from its plastic eyelids. Its skin would have been ripped at some point and I would have stitched it with fabrics found along the way.

My fantasy of a travel companion was never fulfilled, or I should say, it was never fulfilled intentionally. At some point there were many dolls that moved with me, but not everywhere I went. Their hair was not messy from our frantic movements at all, no sand to be found either. It was a collection of dolls that was clean; each one of them experienced some part of my life but not all. They were just there by accident, multiplying; an unintentional hoarding.

Collecting happens through the sensory. We collect sounds through listening; scents through smelling; images through vision. I store memories in my body; voluntarily (pleasure), involuntarily (heartbreak), or both (melancholia). The memories tied to objects, the ones that are sticky enough, transcend their assumed mere dead materiality. They become affective containers.

When I think of an archive I think of a rigorous, intentional collection. I have tried to start an archive of some sorts quite often. For example, I tried to make a drawing of my nightstand everyday and had a designated sketchbook to do so. After three pages the book is blank. I also started collecting paper mache faces. I only have two of them now, getting dusty on top of my closet. My last collection involved making hats. They are nowhere to be found, but I am still hopeful this will unfold.

In starting a new collection there is a wish for a grandiose amount of similar objects. I came to think of this type of repetition as an aesthetic of patience: as if the quantity of the objects signals the temporality and rigour of a successful archive. In this understanding of an archive, a certain amount of patience and discipline seems to be needed in order to truly finish it.

Personally, I seem to have quite the collection of failed archives; an aesthetic, or result, of impatience.

Yet there is rigour to be found there too. It is intense in its hopefulness. It is a collection of potential companions; of interesting movements; or, just so, of wishes.

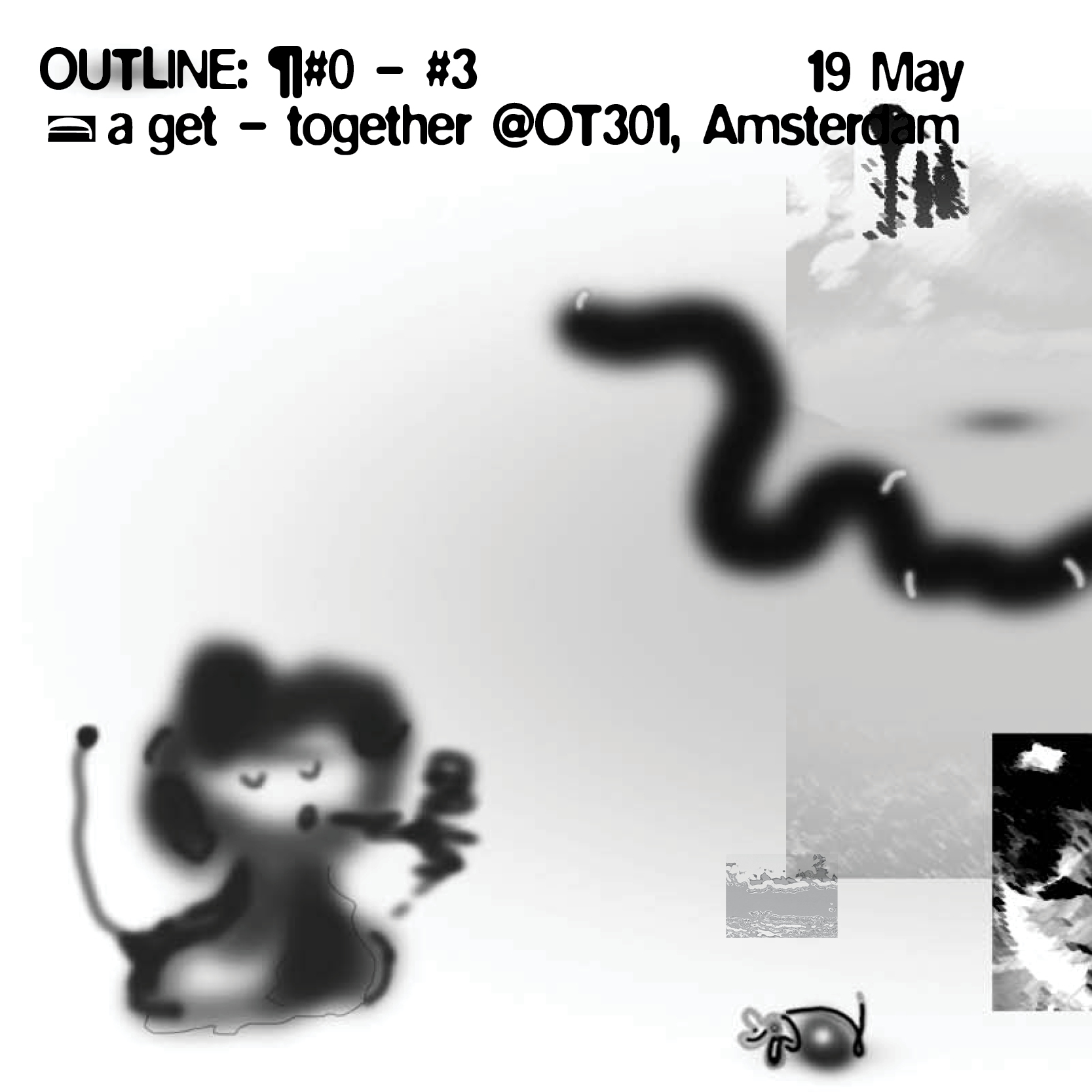

This text was read live as part of OUTLINE ¶#0-¶#3, A get-together in OT301, Amsterdam.