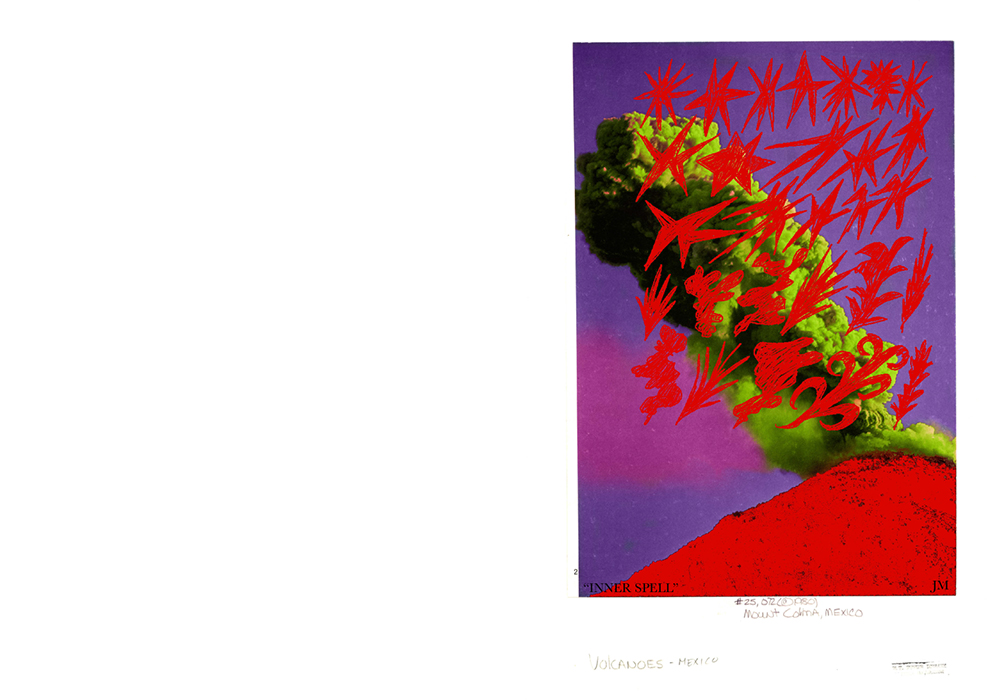

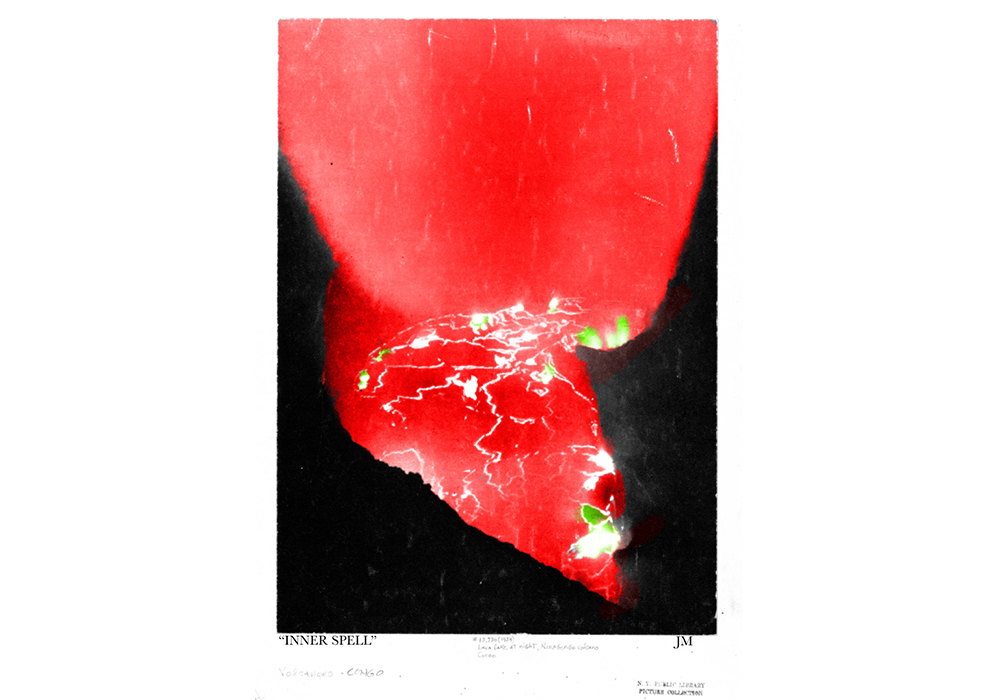

Inner Glow

Jannete Mark

Inner Glow is a glimpse into the ongoing research project that studies the relationship between human body, mind, perception and natural phenomena in everyday life and history. I will share with you some exciting stories that inspire my work, sketches and will show how I apply map-making, archiving, drawing as methods in my work to correspond with the hard/soft tangible thingness of the world with its ethereal and immaterial processes.

The 19th century Russian scientist Vladimir Vernadsky believed that our physical and mental well-being was helped by raising the status of the materialities of which we are composed ourselves, those that we share and use to communicate with the world around us.

“To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour”

– Auguries of Innocence, 1863 W. Blake

CHANGING BODIES

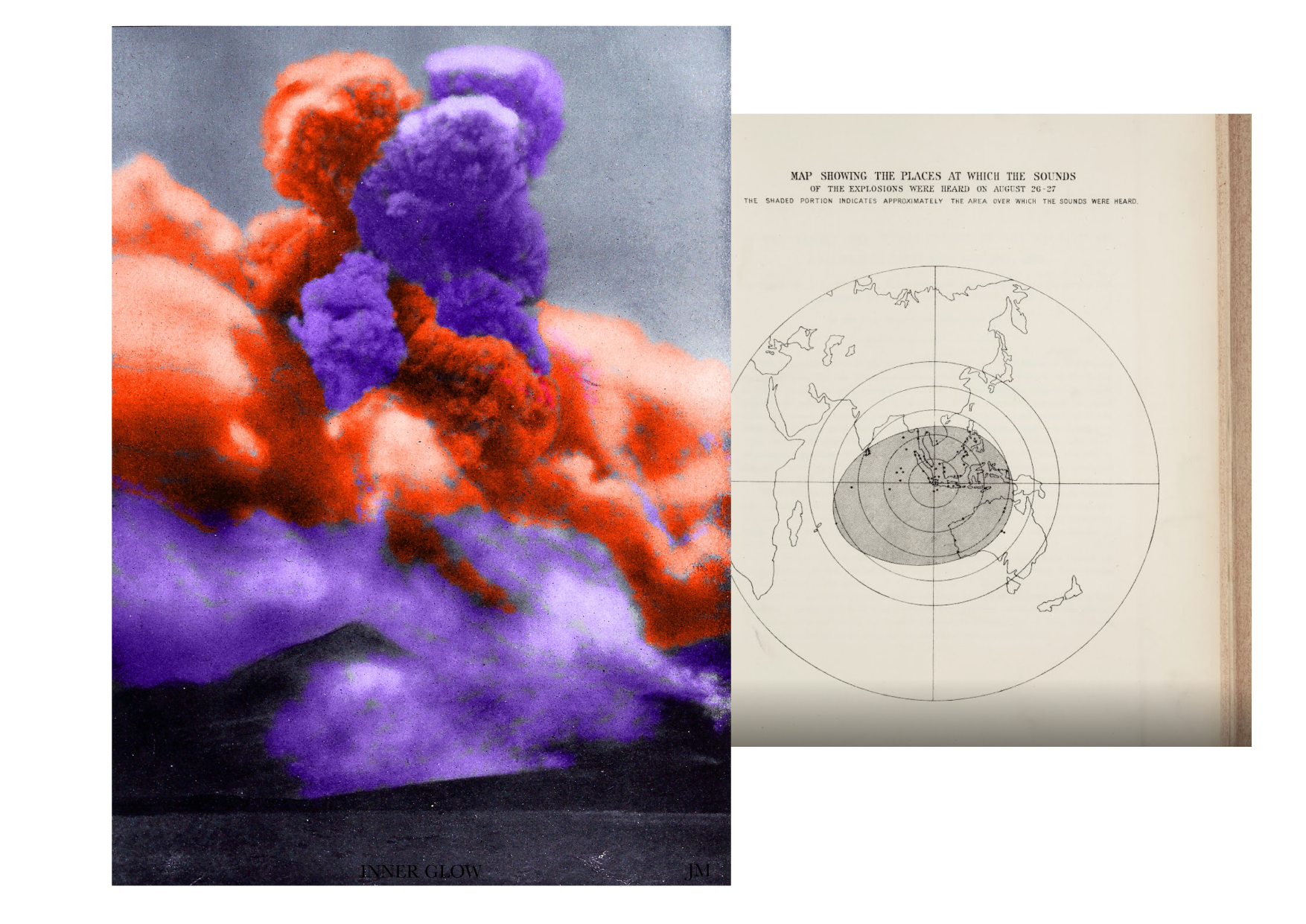

In August 1883, an Indonesian volcano called Krakatoa produced an eruption so large that scientists compared it to a 100-megaton nuclear bomb. It was one of the deadliest volcanic eruptions of modern history. The eruption also affected the climate and caused temperatures to drop all over the world.

Lithograph of the eruption, c.1888

Ash from the Krakatoa explosion rose as high into the atmosphere as 80 kilometres (50 miles). Many of these ash particles can be about 1 micron in size, which could scatter red light and act as a blue filter, resulting in the Moon appearing blue. Blue-colored Moons appeared for years following the 1883 eruption. As a rule of thumb, to create a bluish Moon, dust or ash particles must be larger than 0.6 micron, which scatters the red light and allows the blue light to pass through freely.

Thin sections of the rocks of Krakatoa (1888)

When a volcano Krakatoa erupted, the evening skies of the world glowed for months with strange colours.

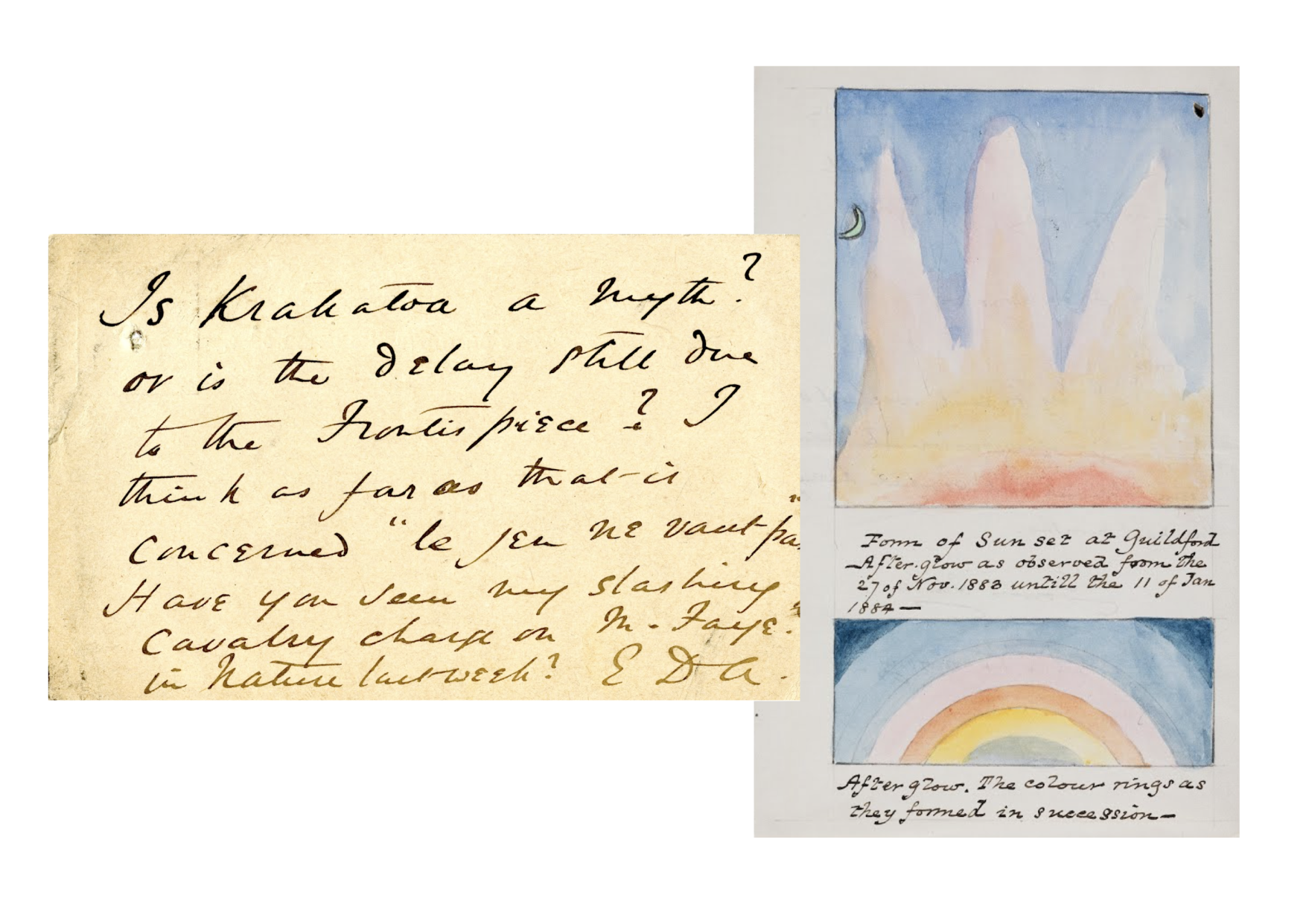

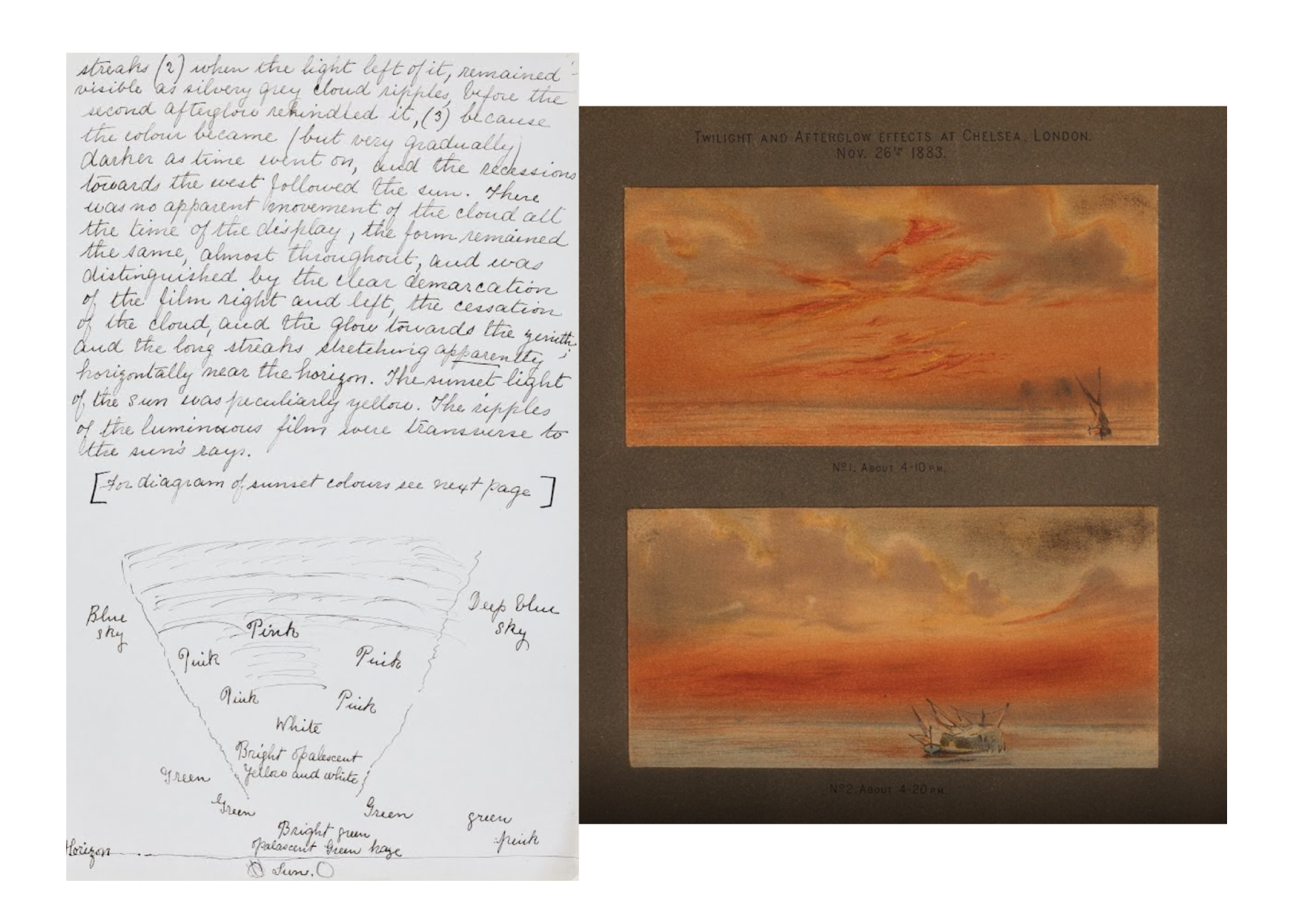

Krakatoa afterglow effects (11 Jan 1884) by Archibald Henry Swinton

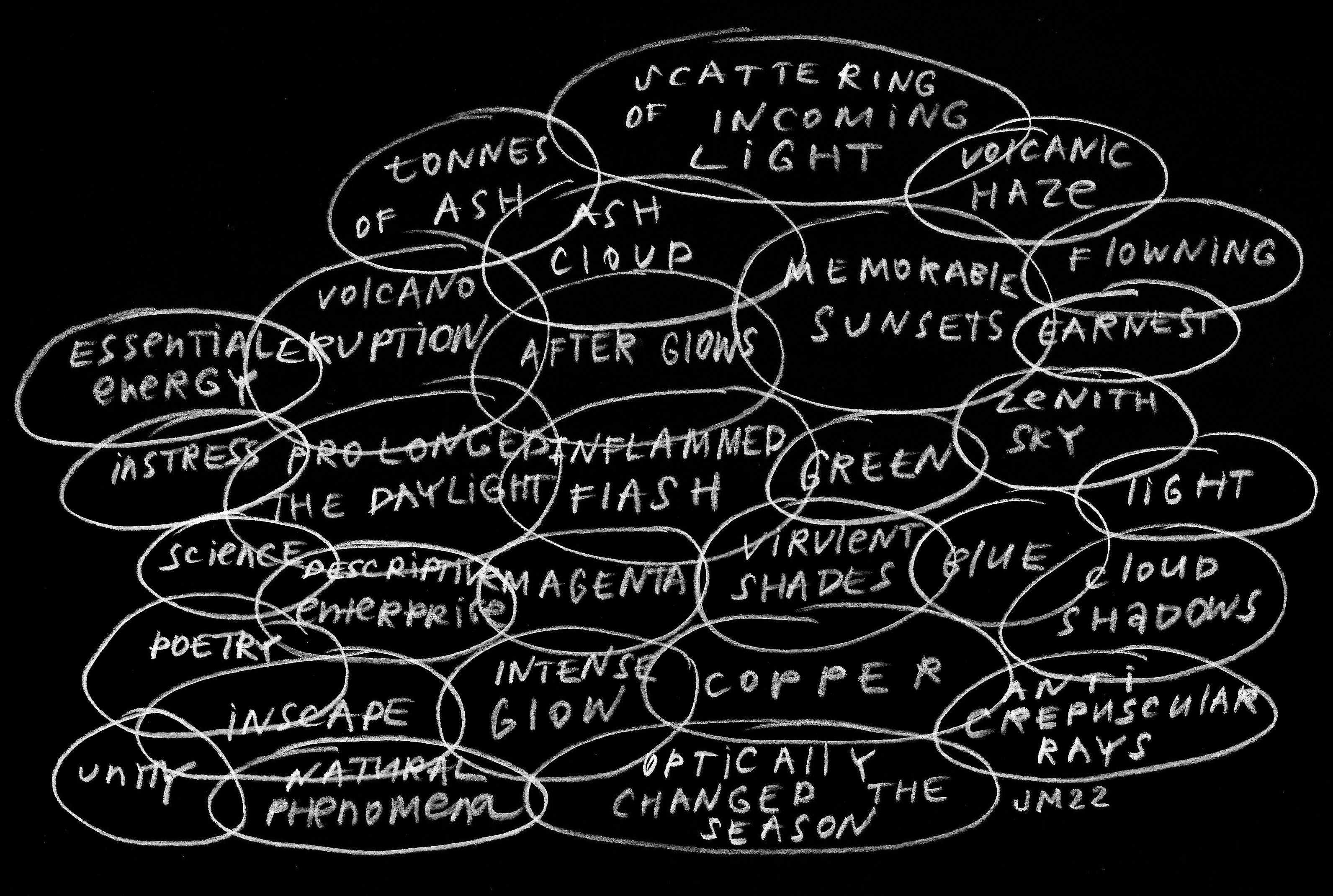

As many other observers at the time, the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins had no idea what was causing the phenomenon, but in fascination he was tracking the changing appearances of the skies for the whole duration of that unsettled winter.

Throughout November and December, the skies flared through virulent shades of green, blue, copper and magenta, “more like inflamed flesh than the lucid reds of ordinary sunsets,” wrote Hopkins; “the glow is intense; that is what strikes everyone; it has prolonged the daylight, and optically changed the season; it bathes the whole sky, it is mistaken for the reflection of a great fire.”

At the end of December, he collated his observations into a remarkable 2000-word document, which he sent to the leading science journal, Nature. His article, published in January 1884, was a masterpiece of reportage.

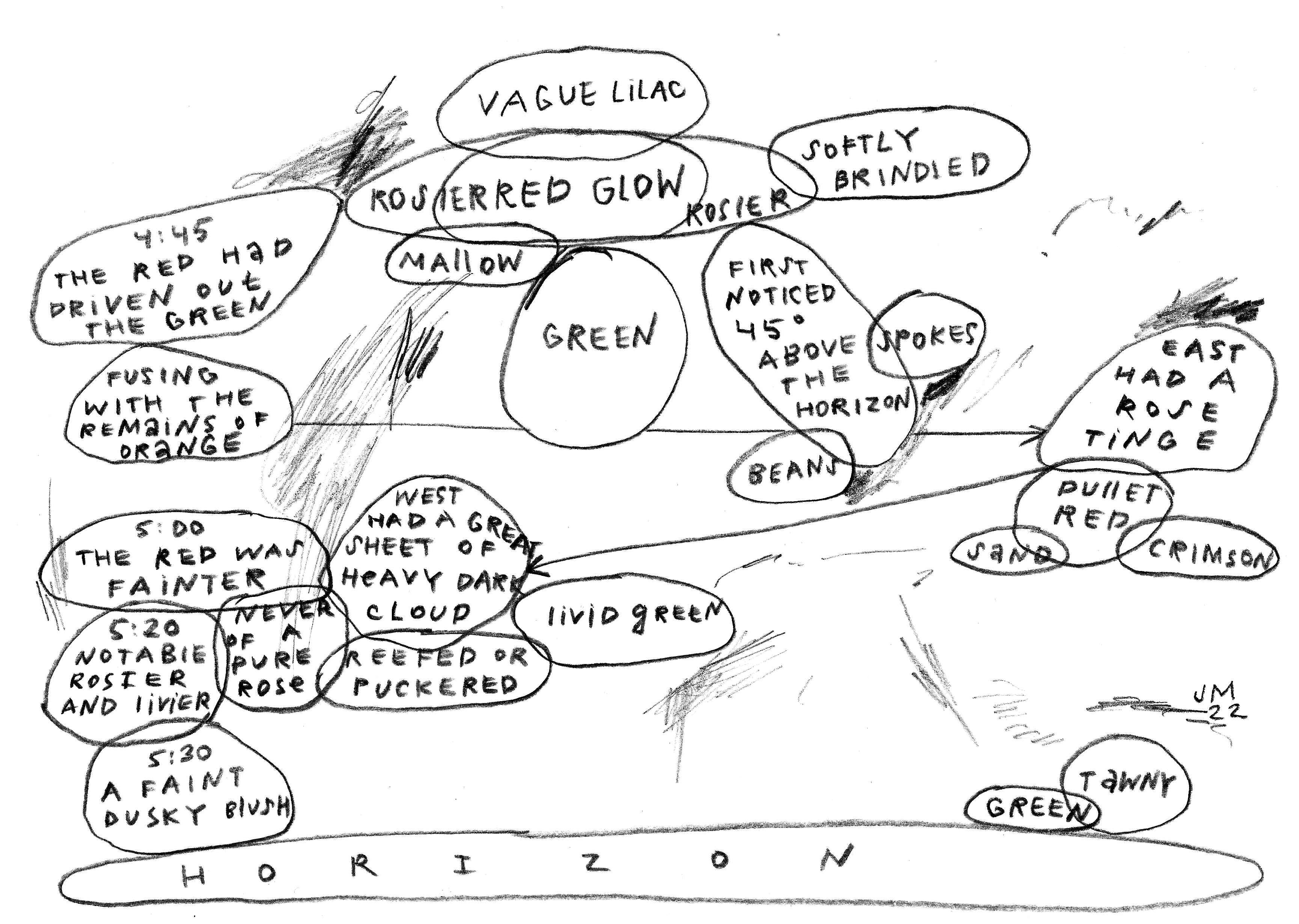

“Above the green in turn appeared a red glow, broader and burlier in make; it was softly brindled, and in the ribs or bars the colour was rosier, in the channels where the blue of the sky shone through it was a mallow colour. Above this was a vague lilac. The red was first noticed 45º above the horizon, and spokes or beams could be seen in it, compared by one beholder to a man’s open hand. By 4.45 the red had driven out the green, and, fusing with the remains of the orange, reached the horizon. By that time the east, which had a rose tinge, became of a duller red, compared to sand; according to my observation, the ground of the sky in the east was green or else tawny, and the crimson only in the clouds. A great sheet of heavy dark cloud, with a reefed or puckered make, drew off the west in the course of the pageant: the edge of this and the smaller pellets of cloud that filed across the bright field of the sundown caught a livid green. At 5 the red in the west was fainter, at 5.20 it became notably rosier and livelier; but it was never of a pure rose. A faint dusky blush was left as late as 5.30, or later. While these changes were going on in the sky, the landscape of Ribblesdale glowed with a frowning brown.” (from G. M. Hopkins, “The Remarkable Sunsets”, Nature 29 (3 January 1884), pp. 222-23)

Hopkins was not alone in his interest; all over the world writers, artists and scientists responded to the drama of the volcanic skies. Alfred Tennyson wrote:

“Had the fierce ashes of some fiery peak

Been hurl’d so high they ranged about the globe?

For day by day, thro’ many a blood-red eve . . .

The wrathful sunset glared . . .” (St. Telemachus, pub. 1892)

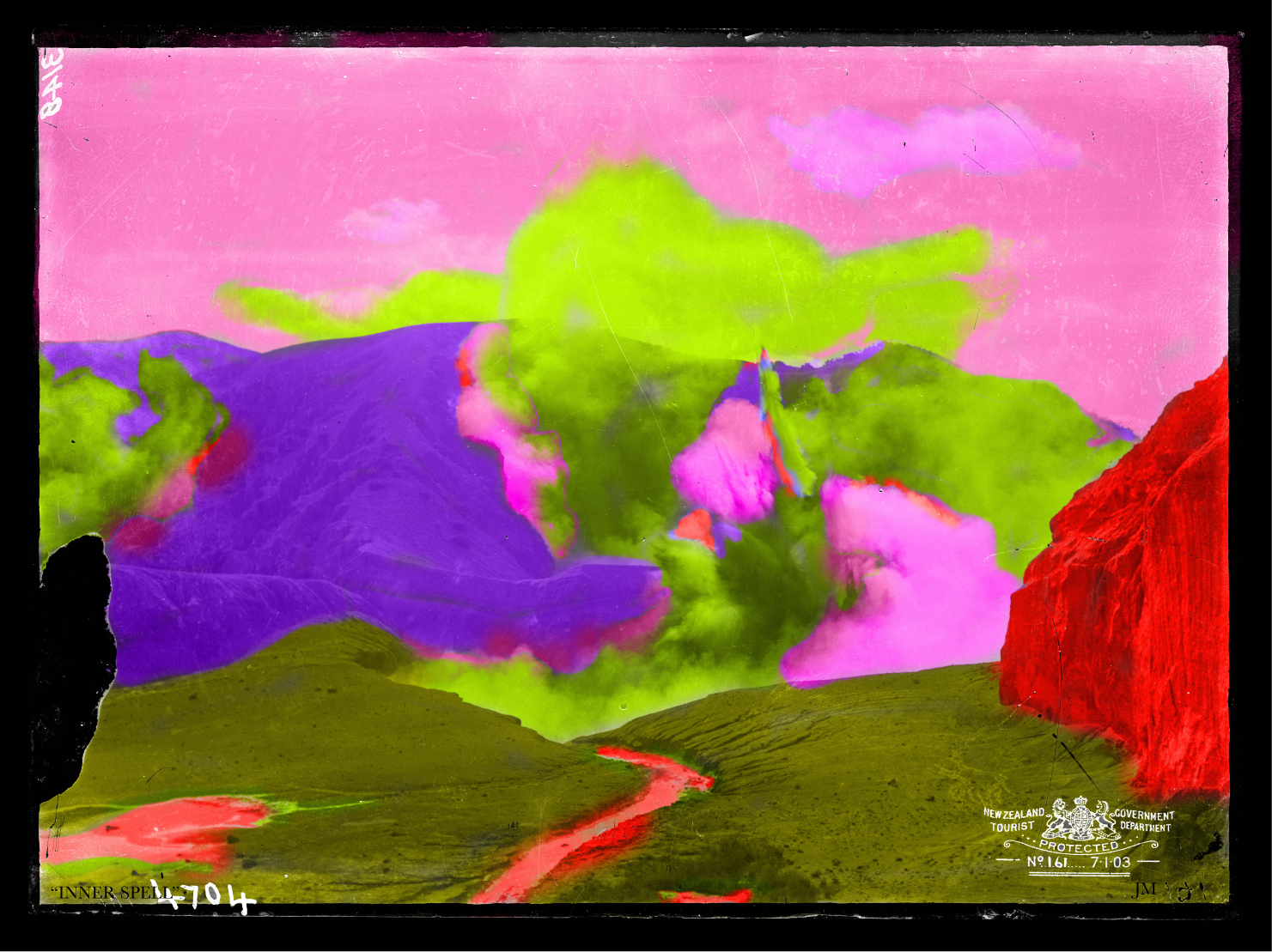

Atmospheric effects of the Krakatoa eruption (1888) by William Ashcroft

In Oslo, the sunsets inspired one of the world’s well-known painting “Scream” (1893) by Edvard Munch, who was walking with some friends one evening as the sun descended through the haze:

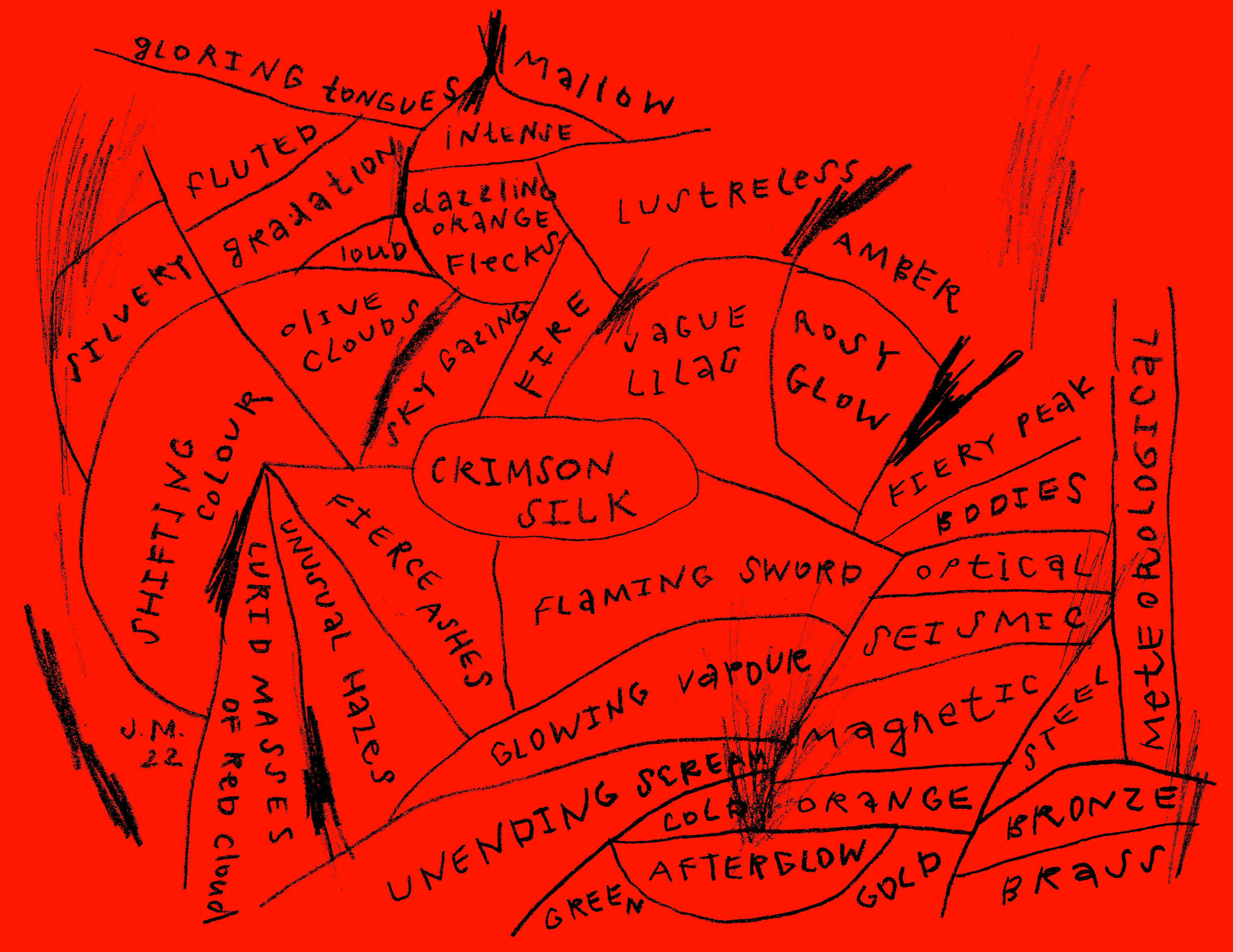

“it was as if a flaming sword of blood slashed open the vault of heaven, the atmosphere turned to blood – with glaring tongues of fire – the hills became deep blue – the fjord shaded into cold blue – among the yellow and red colours – that garish blood-red – on the road – and the railing – my companions’ faces became yellow-white – I felt something like a great scream – and truly I heard a great scream.”

The final eruption of Krakatoa on 27 August 1883 was the loudest sound ever recorded, travelling almost 5.000 km, and heard over nearly a tenth of the earth’s surface.

Sound range of the Krakatoa explosions (1888)