On the remix, dub and publishing in archival institutions

OUTLINE

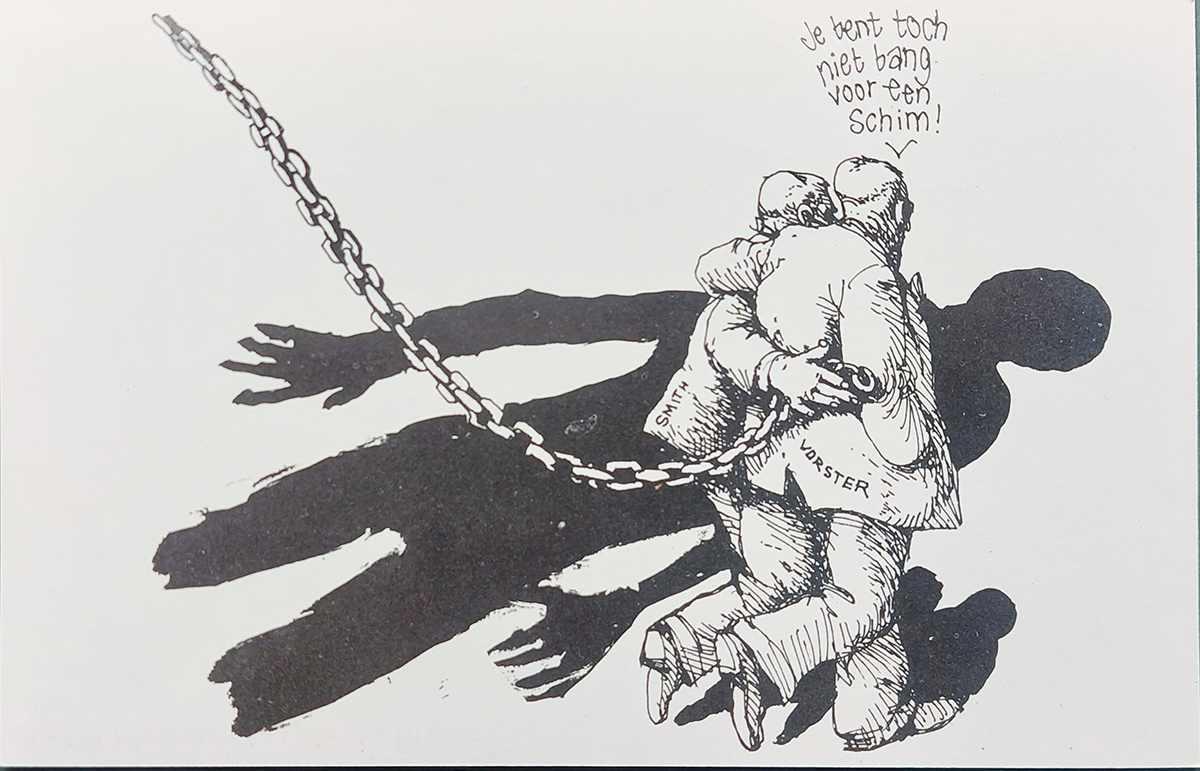

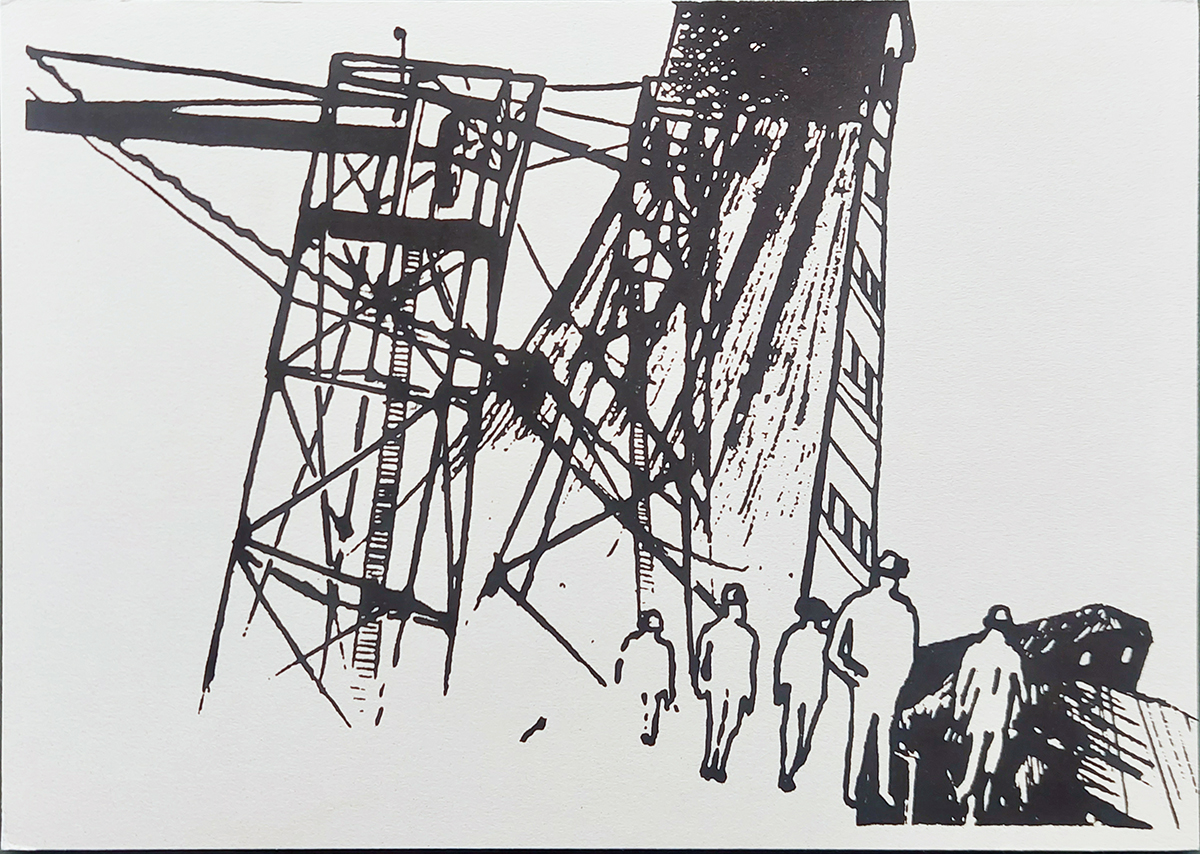

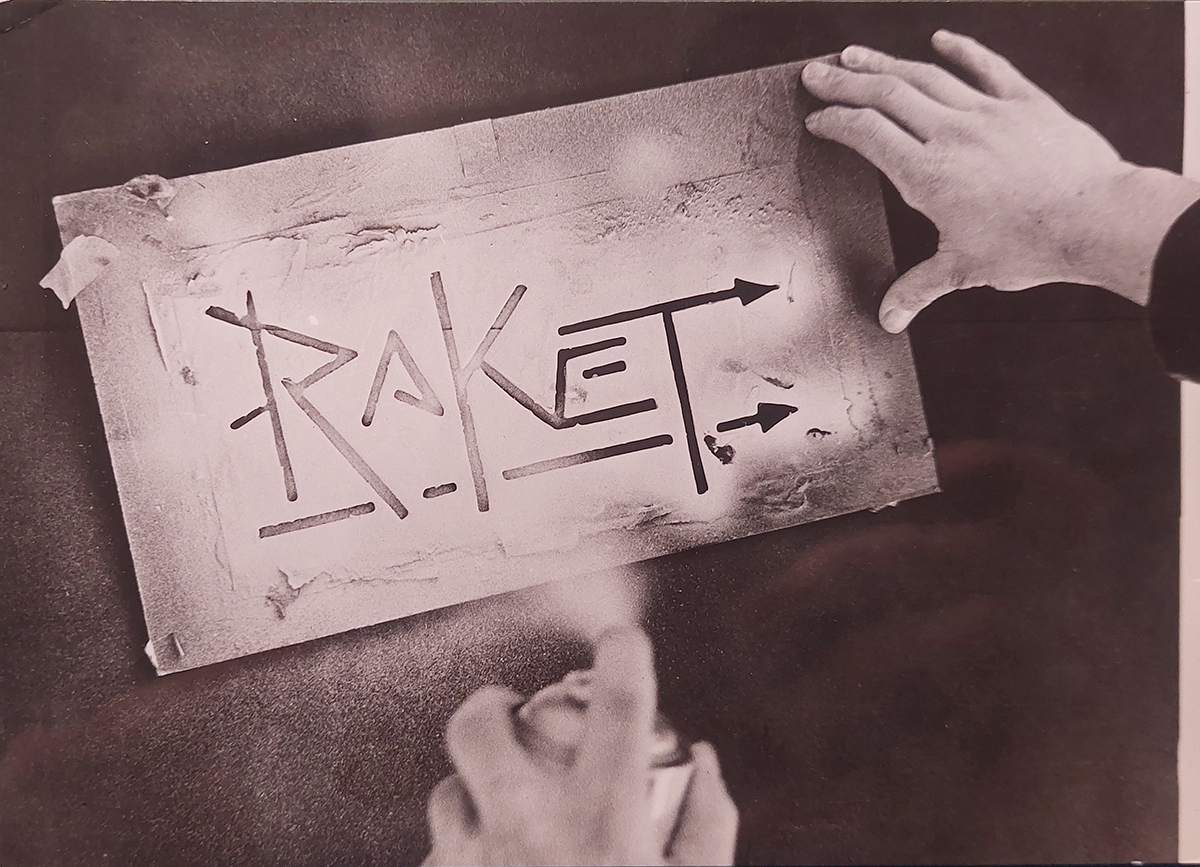

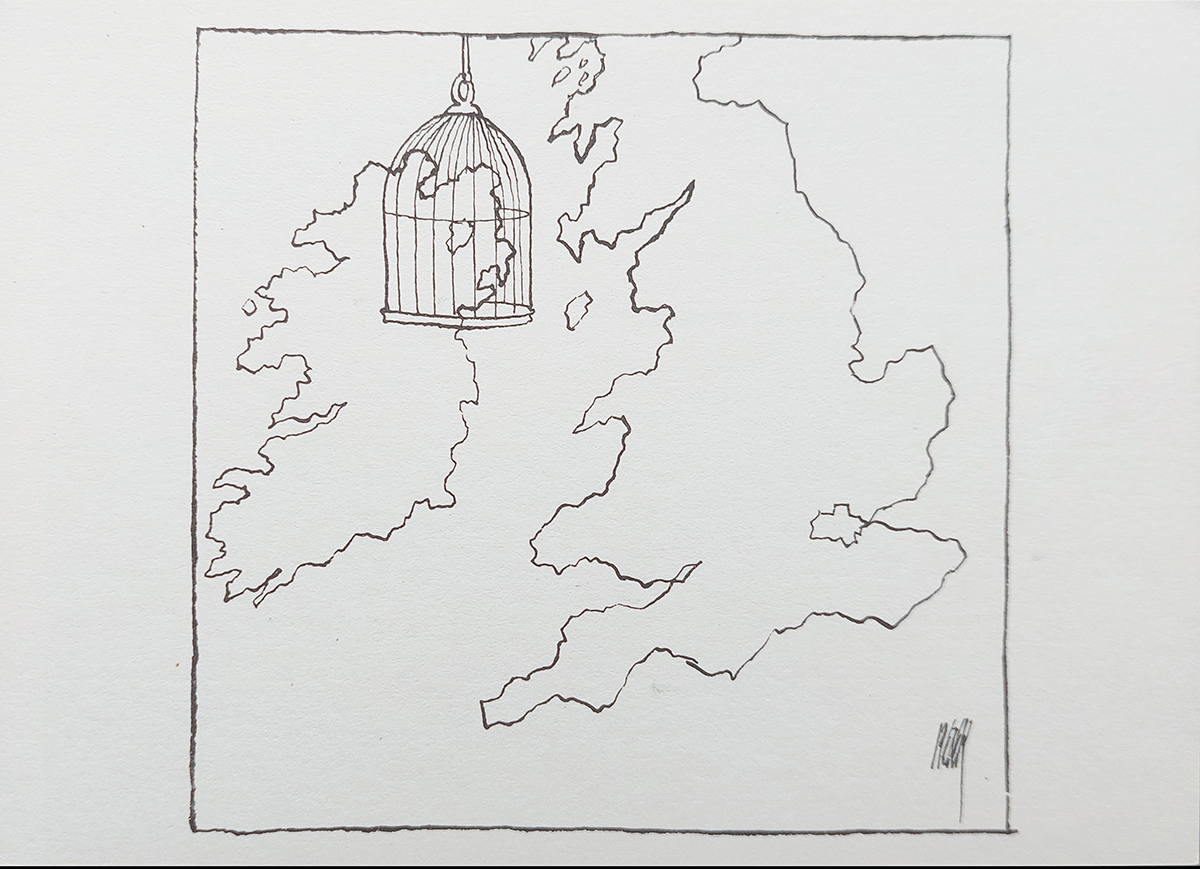

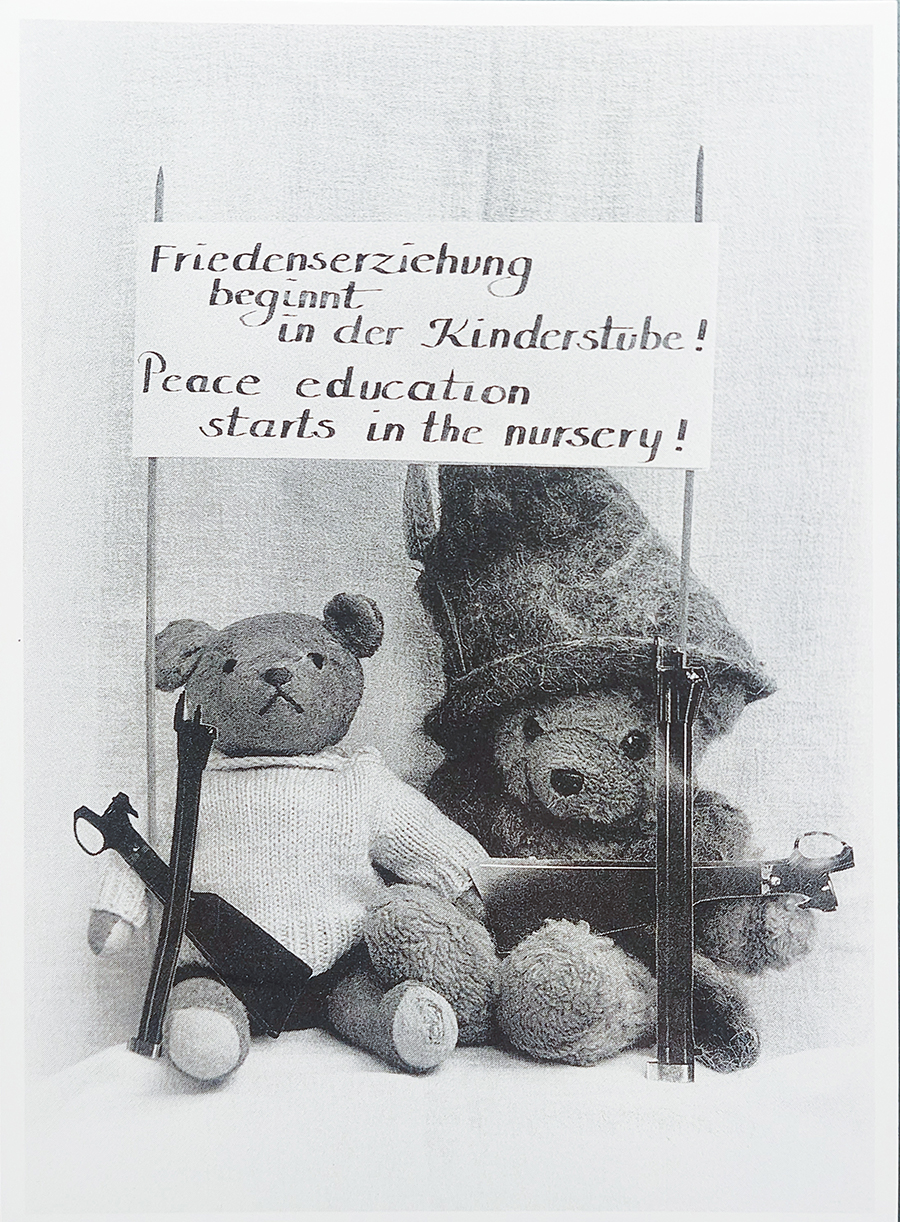

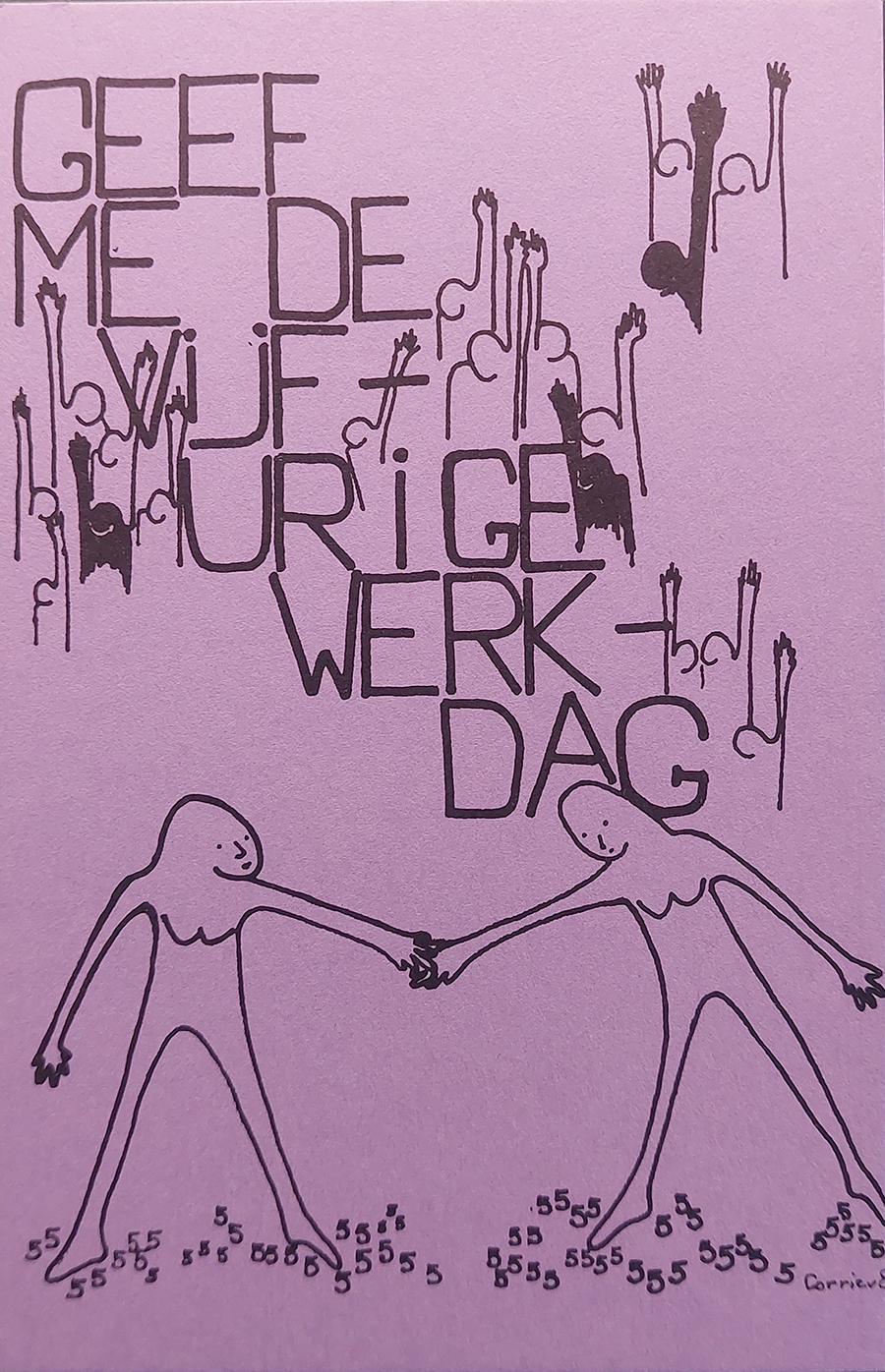

Note on the images:

All images used in this article are part of the postcard collection at the International Institute of Social History (IISH, Amsterdam). This collection holds 1850 postcards from various countries that were published from 1875 up to 2010. Most of them were published for activist or political reasons, by activist groups, artists, NGO’s, unions and political parties. Find more information on the website of IISH or by visiting the collection in Amsterdam.

During our residency period at Network Archives Design and Digital Culture (NADD) we formulated a hypothetical publishing practice in which we, as a publisher, situate ourselves between an archival institution and its potential browsers. This proposal is built on an institutional and financial infrastructure that is not (yet) in place. It is a first hopeful step in an ongoing conversation with archival institutions, possible browsers and potential publics, with future manifestations to come through other project frameworks. In this write-up, we will report on our activities during this 3 month period, but mostly we would like to share parts of our ongoing theoretical and practice-based research that were activated and manifested by this residency, the conversations we had and the objects we encountered.

The archival institution as host and repository

The residency which we were a part of set out to explore questions and challenges around decentralized structures and network culture in an archival context. We responded with a counter-question, how to publish an archive in pluriform?, hoping to find some answers within our own publishing practice to the problematics of verticality, high thresholds (or, even worse, feigned accessibility) and centralized structures in archival institutions. Even though many archival institutions are at least in part available to the public, only a select few—mostly those who have academic privilege—find their way to the objects that they house. Databases are often tricky to navigate and coded with jargon. But perhaps more importantly, it is also a question of pr: many people do not know of the existence of these archival institutions and its public functions. We set out to create a publishing methodology that is transferable and reproducible; one that can be copied, repeated and adjusted by ourselves and others, a tool that is multivocal by default. Our collaborative practice as OUTLINE is based on the gesture of the invitation and the act of publishing. We set out to examine not only the complicated–and potentially problematic–position of the archive (its walls, its selection procedure, its aura of exclusivity) but also the position of the “browser”: the one who gets to enter, look, pick up, research, engage with. The methodology we are developing came from the desire to create an infrastructure through which the archival institution, its collections and its objects are continuously visited and revisited. In this process, we position ourselves between the archival institution and the browser: as inviters, editors and publishers.

In this proposed methodology, the archival institution is our starting point, repository, host, and point of return. Together with different browsers-selectors we aim to make use of its resources and, of course, on the objects it houses in a relationship of mutuality: the archive’s raison d'être lies within its use. In our residency period we have focused on the International Institute of Social History (IISH, Amsterdam), with additional visits to Nieuwe Instituut (NI, Rotterdam). We used IISH—it’s canteen and reading room—as our hub, and met up several times with archivists and other staff members working there. As a publisher, we were interested in IISH as an archival institution that does not primarily collect art or design objects, but objects that subtract their value from their socio-historical context, and not as part of artistic discourse. The IISH houses extensive and valuable collections and dossiers on the histories of communities that are often overlooked and underprivileged; communities whose social histories matter especially because they are generally ignored in violent systems of social and political minorization.

We hosted two workshops at NI and IISH. Due to the open-endedness of the workshop proposal and the research connected to it (more as a result of oversight than of intention, these afternoons turned into conversations with the participants and archivists. The sessions were structured around a selection of archival objects as well as a methodological framework which is based on the following recursive process:

Inviting one or several browsers into the archive through an open call format, forming a temporary collective > browsing the archive together > selecting objects > adding layers of relational meta-data to the selected objects > writing a multi-authored essay > publishing the findings in a quarterly periodical > inviting browsers through an open call based on the findings of the previous periodical > repeat.

Dubbing the archive

Susan Sontag writes: “Each work of art gives us a form or paradigm or model of knowing something, an epistemology." The same can be said for any archival object. With every activation of the archival object another node is created, and another virtuality from the objects’ cloud of potentialities becomes material. We propose to use the archive as a space of (post-)production, building on the Marxist notion that consumption and production are simultaneous processes, and offering a publishing pattern to share the surplus of this consumption-production mutualism. Together with each new temporary collective, we’d like to shape a zine-like publication through a process of communal editing as well as adding a stratum of relational metadata on top of the archival objects: thoughts, conversations, references, anecdotes and speculations. These publications could potentially find their way into places and hands that aren’t easily found or probed by the archival institutions themselves, through intentive distribution schemes and subsequent activation of the printed material through event organizing. The publications propose a kind of shadow archive which attempts to think through the theoretical prompts offered in the essay, formulating reflections and positionalities, but it is also a playful process of formal association and creating non-linear relations between the objects’ past, its current activation and its future potential. Because presenting information in a meaningful way requires the definition (albeit open and multiple) of possible relations between modules. It is through this reflection on connections between modules that alternative forms become imaginable.

With this way of publishing we rely on the musical tradition of dub. Dub is a musical genre that took shape in Jamaica, and grew out of, or on top of, reggae songs. In dub, the original reggae track is electronically manipulated and remixed, usually by taking out the vocals and enhancing the rhythm and bass section, as well as adding new layers of sound. Kodwo Eshun writes:

“Against pop's presence, its realtime voice, dub asserts the logic of the dropout, the song's gravity being plunged into a yawning chasm, of space as an invasive force on the song, x-raying the song structure, disembodying the song, distributing its traces, hunting the ghosts of sonic textures. Dub is the nth-degree warpfactor, the trace element. It disorganizes The Song, subtracts into an apparition, a phantom funk of stealth and intermittence.”

Important to the advent of dub were so called dub plates: wax coated metal plates used in music studios to test recordings prior to the final, mastered track. These fragile dub plates circulated in dub sound systems in an early form of music piracy: they were a way to play exclusive music that wasn’t yet officially released. The plates were often modified, omitting vocals partly or completely. The original track and its aura are repeatedly reborn, versioned, through its modification and reproduction in a network of avid post-producers and listeners. Displacement and alteration keep the track alive without exhausting it.

The term dubbing in sound recording means the “transfer or copying of previously recorded audio material from one medium to another of the same or a different type.” To dub is to record on top of an existing track, or to make a copy of an original. Dub is a process in which meaning is simultaneously dissoluted and distilled, as Michael Veal writes. We propose a rough translation of this process, trading the music studio for the archive, both being rather hermetic institutions that nevertheless reflect the society in which it exists.

The genealogy of a track, or of an object, is always non-linear and eclectic: “Walter Benjamin calls this ‘historicity’, in contrast to historicism, or ‘Jetztzeit’ (‘here-and-now’). What he means by this is that two widely disparate historical events may have more in common than two events close together in time. This historicity is ever-present, aligning the past with the here and now – and so also with the future."

How to dub an object? How to extract and annex value, and how to make this value resonate outside of the archives’ walls? By situating ourselves in relation to an object we cast a shadow somewhere else, depending on the position we take in relation to the particular object. With this in mind the shadow archive becomes a subjective and speculative form of relating to the existing archive.

Relational archives

For this proposal a kind of ongoing relationship with the archival institution is needed; an infrastructure of attention and dedication between the host (the archive), the intermediary (the publishing platform), the temporary collectives, and the reach of potential publics through distribution. Part of the care lies in the ongoing process of carefully constructing invitations and in the persistence of returning to the institutional host, upholding a conversation over a prolonged period of time. This is not just a matter of care, but of funding as well. There is an abundance of artistic interventions and experimental research done in archives, many of which are potent and interesting, but without a lasting impact because of an absence of longer-term monetary frameworks within which ideas can be nurtured and elaborated. Our proposal will, for now, remain just that: a proposal, a prototype.

Michel Foucault’s thinking around relational knowledge is useful to keep in mind while exploring relationality in artistic production and archival reproduction. In his lectures series The Hermeneutics of the Subject Foucault discerns two types of knowledge: through causes and through relations. Causal knowledge is a knowledge based on tracing a subject: it looks at a subject by itself, isolated from its environment. Relational knowledge maps a subject within its surroundings, its linkages. It doesn’t assume a sovereign production of meaning, and it doesn’t reduce meaning from a single origin but from its relations, drawing out in all possible directions rather than attempting to fabricate linearity or continuance. Relational knowledge is useful: it doesn’t just deal with “facts” but tries to understand surroundings and situations, it is translatable into “prescriptions.” Foucault doesn’t necessarily offer a critique of any type of knowledge, but of ways that this knowledge can be used. Or better, it critiques the lack of use of knowledge; knowledge that is “ornamental, typical of the culture of a cultivated man who has nothing else to do.” Instead, knowledge should equip us for our future encounters, for figuring out the meaning of relations and formations. It should be lived, embodied, and used, and thus naturally fed back into the community.

Marx writes: “Consumption is simultaneously also production, just as in nature the production of a plant involves the consumption of elemental forces and chemical materials.” An (art, archival, paraphernaliac, collectable) object exists only as an object when it is consumed, looked at, related to, appropriated. To punctuate this idea, art historian Nicolas Bourriaud uses the analogy of the flea market. He uses the analogy in twofold: both as a method (recycling) and as an aesthetic (chaotic arrangements). In this way, the existing objects aren’t used in a way that dissents, unlike in the Situationists detournement, in which capitalist objects are hijacked and subverted, and unlike the readymade, in which the point is to keep the object physically unmodified. The flea market instead “makes material the flows and relationships” of the objects. In the flea market, this flow of the pre-existing is not to devaloraze or revalurize, it is rather a “neutral, zero-sum process” in which “[objects] are no longer perceived as obstacles but as building materials.” Bourriaud’s remix suggests a path away from linearity, away from the search for new territory—and into a more circular way of thinking about the creative process. The remixer’s task is not anymore to be divergent and separate, but to find linkages, to look at the in-betweens. An archival object, then, becomes a proposal of linkages in the midst of constant movement, and the archive becomes a space for production.

The archive and the remix

Paul Ricœur writes: “Forgetting remains the disturbing threat that lurks in the background of the phenomenology of memory and the epistemology of history.” This fear evolves into the lack of imagination on the political left (as well as on the political right, but they tend to have a better way of hiding it, offering easier solutions to today’s and tomorrow’s problems). The pull of the distractions of the past is undeniable too. In the unfinished introduction to Acid Communism, Mark Fisher refers to a truist remark in The Heart Goes Last: “The past is so much safer because whatever’s in it has already happened. It can’t be changed: so, in a way there’s nothing to dread.” But, he continues, “Despite what Atwood’s narrator thinks, the past hasn’t “already happened.” The past has to be continually re-narrated, and the political point of reactionary narratives is to suppress the potentials which still await, ready to be re-awakened, in older moments.” This may be an obvious point, but it is nevertheless an important one. Our sense of time and place is constantly breaking down through memory, locality, mediation, and the urgencies of the present. Maybe we can avoid nostalgia and reactionism through an awareness of this fragmentation, and use these fragments as building stones rather than attempt to revive a past that never was.

These fragments are to be found in archival institutions, and it is through dubbing and remixing these materials that we can come to new understandings. A remix done well, one entrenched in the ongoing and the topical, is always more than the sum of the past. The remixer wonders why some sounds from decades ago are more urgent than ever, and why other sounds released yesterday sound absentminded and superfluous. The remixer examines different possibilities of placement, wonders what it means to nest an object in between other objects, examines this correlation and co-relation, and knows when and where an unseen cloud of virtualities is unpacked, when a new meaning is created through the linkages. Then and there, unforeseen ghosts of the past come out and reverberate into the future. The diffusion and fragmentation of culture has a potential for the remix artist: they can now find new linkages and create connections between the cultural products of the past that are not fantasmagorical but deliberate. The potential problematics of the remix are at the same time its most interesting potential: to see it as a subjective, political historiography, as a proposition for rethinking and rewriting the past through the lens of the present, with a desired future in mind. The artistic and political task of the remixer is to live within this complexity, with an understanding that we live surrounded by relics of the past and by what they represent; its implications, ideologies. It is the undertaking of figuring out what belongs where, what to get rid of and what to underline. To remix is to write with time and similarly to rewrite time.

Édouard Glissant said: “...you can be with the Other, you can change with the Other while being yourself, you are not one, you are multiple, and you are yourself. You are not lost because you are multiple. You are not broken apart because you are multiple.”

The question, then, is: how do we collect, cite and reference carefully, how can we make the citations and references visible, and how can we care for both the materials, their producers and the audience? The question, perhaps, lies in how we can be with the Other without harming this Other, how to be multiple without being in someone else’s way, how to embrace difference in order for it to become a relation. And sometimes something is better left unmixed, or left alone by this person, in that particular space and time. Sometimes a material is too fragile or too complex, sometimes it first needs another life on its own before it is displaced. But in a remix that is well done we can relate to the collected materials and mold them without wounding them; by studying them, loving them, caring for them. The materials become monads that carry in itself a piece of the world. Ownership and re-distribution becomes a kind of intimacy, a kind of living through these materials. Walter Benjamin writes: the “inveterate collectors of books prove themselves by the failure to read these books.” But we would rather argue for the opposite: collectors and remixers prove themselves by reading their materials, they don’t de-value, but firstly value and then re-value these materials.

In our current research and publishing practice, following the residency period at NADD, we’ve been continuing to think through questions around remixing and dubbing in relation to archival objects and other (material or non-material) objects of appropriation. So far, this culminated in a reading- and listening session at Enter Enter (Amsterdam) during BYOB Art Book Fair and a bootlegging workshop at Onomatopee (Eindhoven) during Dutch Design Week. In January 2024 we will present a small publication, accompanied by a sound piece, at the Institute of Network Culture’s Expanded Publishing Fest in OT301 (Amsterdam).

To be continued.

We’d like to express our gratitude to Frederique Pisuisse, Hrafnhildur Helgadóttir, Piet Langeveld, Alexandra Barancova, Thijs van Leeuwen, Ellen van Veen, Dakota Guo and Clara Stille-Haardt for sharing their thoughts, ideas and time for this project.